Why is global climate change a problem?

What the science says...

| Select a level... | Basic | ||||||

|

A large amount of warming is delayed, and if we don’t act now we could pass tipping points. |

|||||||

Global warming is an increasingly urgent problem. The urgency isn’t obvious because a large amount of warming is being delayed. But some of the latest research says if we want to keep the Earth’s climate within the range humans have experienced, we must leave nearly all the remaining fossil fuels in the ground. If we do not act now we could push the climate beyond tipping points, where the situation spirals out of our control. How do we know this? And what should we do about it? Read on.

James Hansen, NASA’s top climatologist and one of the first to warn greenhouse warming had been detected, set out to define dangerous human interference with climate. In 2008, his team came to the startling conclusion that the current level of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) is already in the danger zone.

Since the Industrial Revolution, atmospheric CO2 has increased from 280 to 390 parts per million (ppm). Don’t be fooled by the small number – 390 ppm is higher than CO2 has been in millions of years. CO2 is rising by 2 ppm per year as we continue to burn fossil fuels. To stabilise the Earth’s climate, we must reduce CO2 to the relatively safe level of 350 ppm. And we must hurry, because the task will soon be an impossible one.

The 350 target is based not on climate modeling, but on past climate change (“paleoclimate”). Hansen looked at the highly accurate ice core record of the last few hundred thousand years, sediment core data going back 65 million years, and the changes currently unfolding. He discovered that, in the long term, climate is twice as sensitive in the real world as it is in the models used by the IPCC.

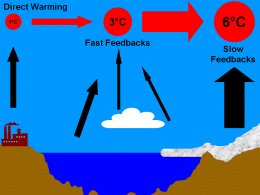

The key question in climate modeling is how much global warming you get from doubling CO2, once all climate feedbacks are taken into account. A feedback is something that amplifies or cancels out the initial effect (eg. interest is a feedback on a loan). The models include “fast feedbacks” like water vapor, clouds, and sea ice, but exclude longer-term “slow feedbacks” like melting ice sheets (an icy surface reflects more heat than a dark surface).

Both models and paleoclimate studies agree the warming after fast feedbacks is around 3°C per doubling of CO2. Slow feedbacks have received far less attention. Paleoclimate is the only available tool to estimate them. To cut a long story short, Hansen found the slow ice sheet feedback doubles the warming predicted by climate models (ie. 6°C per CO2 doubling).

|

Anticipatory Policymaking: When Government Acts to Prevent Problems and Why It Is So Difficult (Routledge Research in Public Administration and Public Policy) Book (Routledge) |